Bursa is a city of whispers. When you look from the plain toward Uludağ or from the edge of the road climbing the mountain back toward the plain, the scene before you may not seem too different from other cityscapes you`ve seen before. But if you go beyond simply looking and pause for a moment to listen, you`ll realize you`re standing on the banks of a whispering river—one that carries deeply buried secrets and hidden sorrows, murmuring softly from stone to stone. These whispers reverberating off bricks, stones, fountains, and domes are not carried to you by the southern winds sweeping down from the mountain, nor by the minarets standing tall across the city, nor even by the ancient plane trees and dusky cypresses greeting the breeze.

If you manage to lose yourself in it, you will feel as if you have left your body behind, carried along by the whispers, drifting from one end of Bursa to the other—from Çekirge to Muradiye, from Muradiye to Tophane and Yeşil, and from Yeşil to Yıldırım. And if you have truly made an effort to understand what these whispers are saying—if you have stood face to face with those who strive to share their secrets and sorrows with you—then, when you return to your body, you will find that atop your shoulders sits an observatory, its windows thrown wide open, gazing at the horizon in every direction; before your eyes, an enormous lens helping you see everything more clearly and truthfully; and within your chest, a heart struggling to break free from its cage, stained with the rebellion at its edge.

If you pass through Bursa without listening to these voices, for example, you will never again, anywhere or at any time, have the chance to learn that the princes did not enjoy jumping rope. You will leave without ever discovering that they spun their tops without a cord, carrying on to wherever you are headed.

The sight of nooses swaying from the thick branches of century-old plane trees—

It is because of the princes who said, "We never swung on swings either."

The burning sensation at your neck, the feeling of separation at your waist—that is why. It is the shared burden of sorrow, and it can only be felt when you listen to the whispers of Bursa

As you are swept along by the current of voices, you suddenly feel a tiny hand grasp your finger. You bend down and find, at your knee, a small prince—searching for someone to trust, his eyes revealing that need more than anything else.

For a moment, you feel as though you have fallen into two deep wells filled with swirling waters.

Tracing the contours of his face with his index finger, he says:

"We were born beautiful."

"We were born beautiful, but our beauty never made our mothers smile. Because they knew something we did not. They nursed us for a long time. When their milk ran dry, they found wet nurses. They knew that once we were weaned, our faces would change—that we would begin to drink in the pale yellow of the palace."

Without seeing the small, discarded sarcophagi—cast aside at the feet of the grand, awe-inspiring tombs—without hearing the whispers rising from them, you cannot understand the feeling of unease that drifts through this child`s eyes, slowly turning into fear.

Seeing you speak with him, another prince approaches and says:

"We were children without games."

"They taught us fear first—and then that games cannot be played with fear."

His voice is hoarse, as though struggling to pass a knot in his vocal cords. If you look closely, you will notice him swallowing with difficulty, and you will understand why his voice emerges only as a whisper.

"We grew up within windows that allowed us to see the doors—and those who entered through them," one of the princes who never truly grew up will tell you.

In another place, from another prince, you hear:

"Our mothers never allowed us to sit on two cushions stacked together; they feared we might grow accustomed to high places. The higher our heads were, the closer they thought we would be to the noose."

And as you listen, you begin to realize that all princes lived the same life, that their voices were one and the same. That what those in power gave them was only fear and death—and that this had never changed.

As you reflect on this, you hear another voice, firm and resolute:

"The others were afraid too," someone says, raising their voice.

"They feared just as much as we did—perhaps even more. It was their fear that killed us."

"We were always on edge; we slept with one eye open and woke by cautiously opening the other," murmurs a prince, barely audible.

"We gazed at the light shining through the square iron grilles of the windows, struggling to believe that a new day had truly begun. Then we would shut our open eye and give thanks. One hand would search for the other, longing to know our fingers were there—there and warm. And that our heads remained upon our necks."

These whispers, which leave you dizzy, bounce off the domes, echo beneath the arches, weave through the columns, and inevitably find you in a corner—standing before you.

As the muezzins recited the call to prayer in piercing tones, the echoes spread from Bursa’s mosques to every corner of the city. In reverence, they would fall silent, waiting respectfully. Once the sounds of the azan withdrew beneath the domes, they would resume their whispers from where they had left off

You would mix up the voices of Şehzade Savcı Bey calling from Tophane and Şehzade Yakup calling from Çekirge. But after listening for a while, you would realize that they were saying the same thing. Both are blind; both were killed blind, and that is what they are telling you.

"We are the first," said Savcı Bey, searching for his way with his cane, "What follows is merely the unraveling of a fabric whose stitch has slipped."

Bursa feels like a stage, as if you are watching preparations for the final act of a tragedy. The whispering chorus, weary in their white costumes, sings the refrain of the only song they have memorized—one last time. The lights suddenly turn on, the play is over. Evening has fallen. Overcome with an unbearable curiosity to learn about the identities of the whispering voices, you rush to magazines, books, brochures, encyclopedias. And you see that the only ones speaking are those in power, and the ones spoken about are the powerful.

Those who try to reach you with their small whispers are nothing more than one-dimensional shadows, confined within the definition of "detail."

They have been given a place—a space of their own. In other words, they have been scattered across a silent sea like shoreless islets.

In books, you come across these lines describing their resting places:

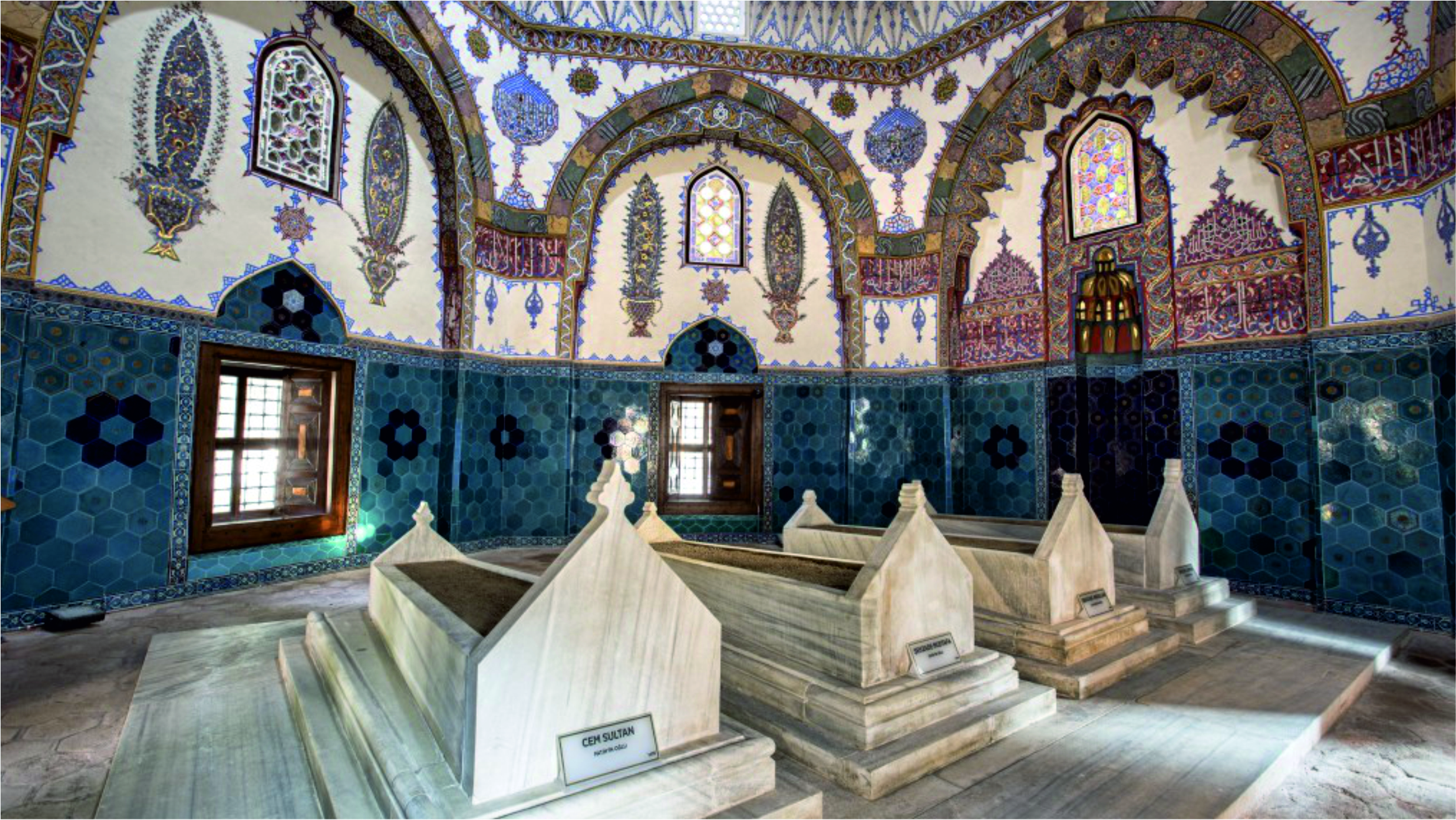

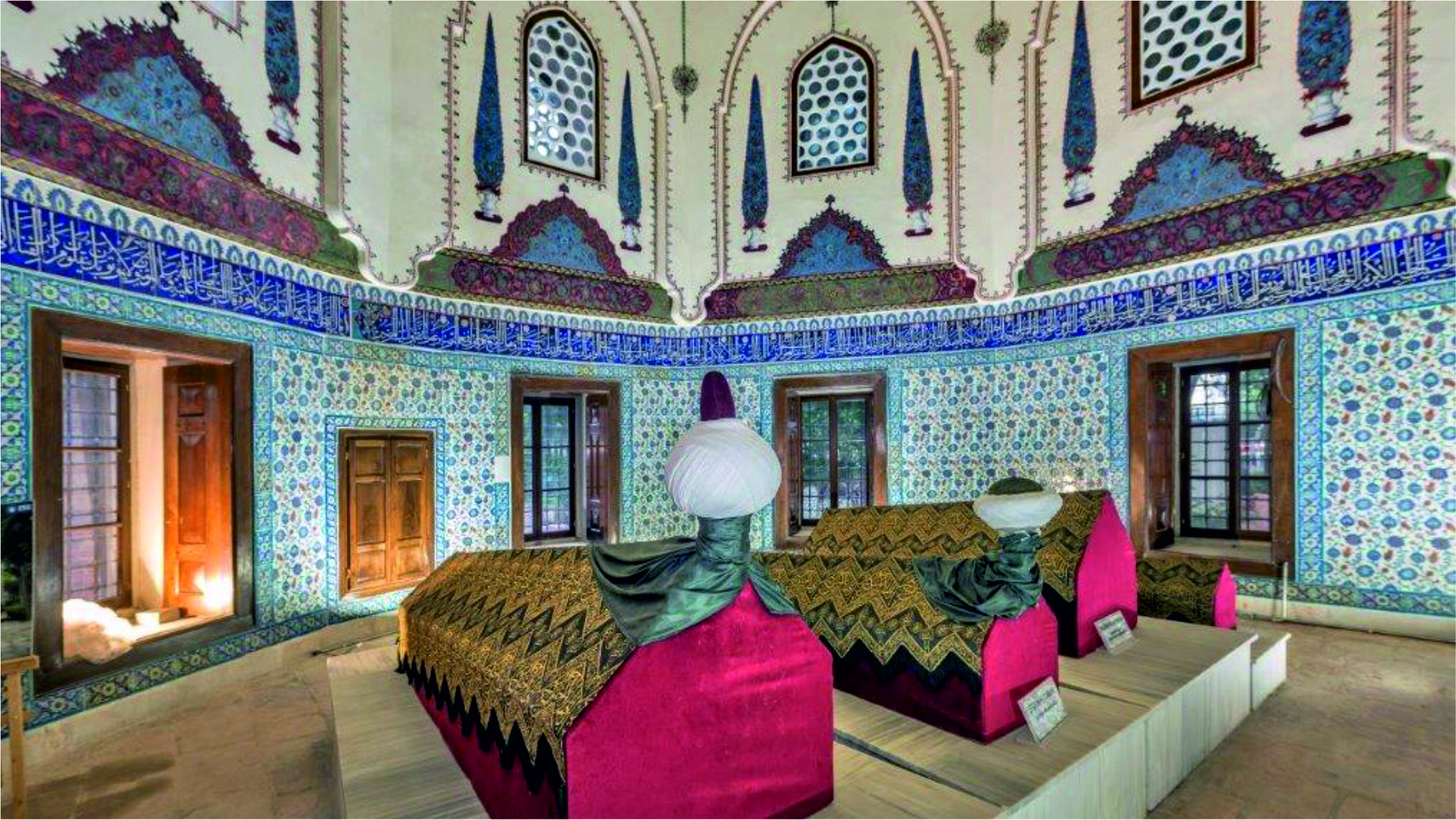

The walls are built with one row of cut stone and two or three rows of brick. The doors feature interlocking wooden panels, often adorned with a diamond pattern. The tall windows are stained glass. Ground-level windows have wooden shutters and deep recesses. The domes are supported by columns. The interior walls are decorated with İznik and Kütahya tiles, with mother-of-pearl inscriptions embellishing the tiles. The sarcophagi take the form of triangular prisms..

Your readings are not enough—you want to see these places for yourself. And this time, you find that the whispering voices are nothing more than brass plaques. Upon the plaques leaning against the sarcophagi, the names are written: Şehzade Orhan, Şehzade Musa, Şehzade Emir, Şehzade Osman, Şehzade Ahmet, Şehzade Mehmet...

But it is never written that these princes lie there because they could not jump rope.

It is never written that they are the transparent heroes of a tale flowing from the curtain of dreams.

It is never written that, even if their turn came, they would not be able to speak.

It is never written that their monologues are silent and sorrowful, their endings devoid of applause.

They rise onto their toes, and with the last voice in their throats, they declare:

"Tomb!"

Source: Saat Bursa Suları, pages 31, 34 Nuri Demirci